When we think of advanced technology, we often picture modern inventions. But our ancestors were far more ingenious than we give them credit for. We’re still learning from them today. Once you start going down the rabbit hole of ancient technology, you’ll be amazed by what our ancestors invented. Sadly, much was lost to time and only “reinvented” many hundreds of years later. Let’s explore some amazing ancient technologies that were centuries ahead of their time, showing just how clever our forebears really were.

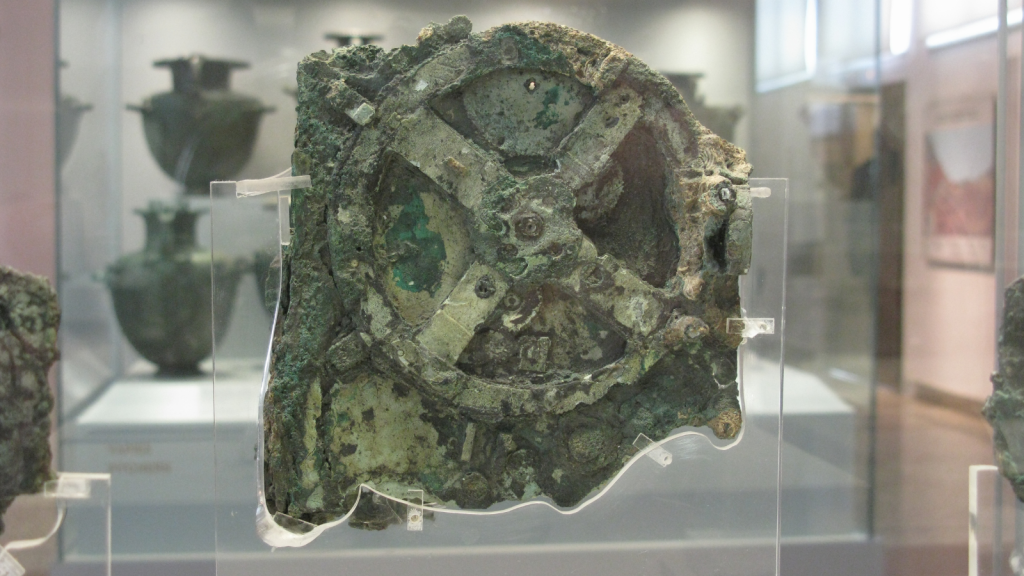

The Antikythera Mechanism

Discovered in a shipwreck off the Greek island of Antikythera, this device is often called the world’s first computer. Dating back to around 100 BC, it could predict astronomical positions and eclipses with remarkable accuracy. The mechanism used a complex system of bronze gears, way more advanced than anything else known from that time. Its discovery changed our understanding of ancient Greek technology and engineering skills.

Roman Concrete

The ancient Romans created a type of concrete so durable that some of their structures still stand today, 2,000 years later. Unlike modern concrete, which can crumble within decades, Roman concrete gets stronger over time. The secret? A mix of volcanic ash, lime, and seawater that triggers a chemical reaction, filling cracks with new minerals as they form. Scientists are still trying to fully understand and replicate this amazing material.

Damascus Steel

Medieval swordsmiths in the Middle East produced blades of legendary sharpness and strength. Damascus steel swords could slice through rock and remain razor-sharp. The exact technique for making them was lost around 1750 AD. Modern attempts to recreate Damascus steel haven’t fully matched the original. Some think the secret might lie in trace elements from specific ore sources no longer available.

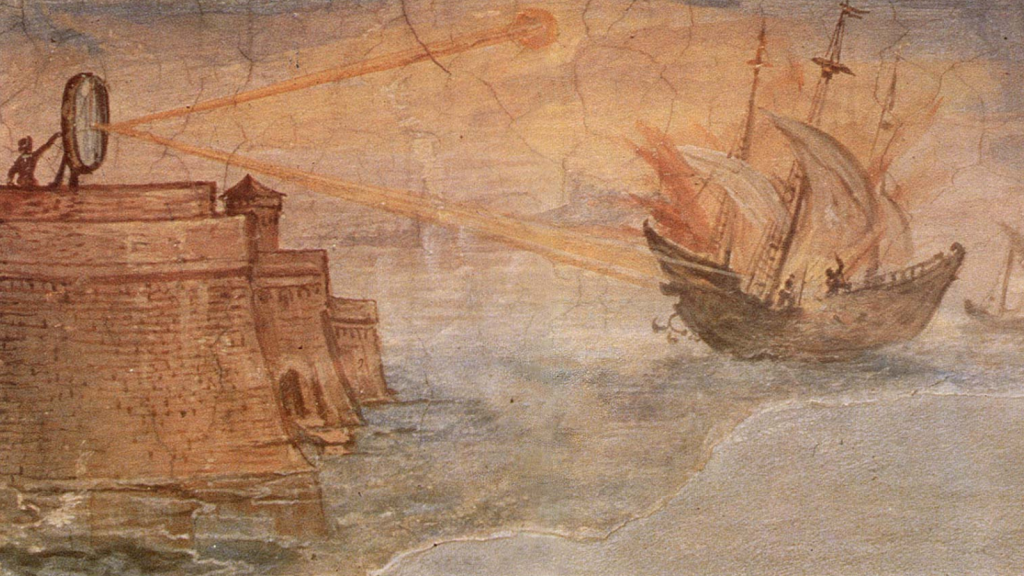

Greek Fire

This was a mysterious incendiary weapon used by the Byzantine Empire. It could burn on water and was almost impossible to put out. Greek Fire gave the Byzantines a huge advantage in naval battles. The exact formula was a closely guarded secret and has been lost to time. Historians and scientists have tried to recreate it based on ancient descriptions, but its true composition remains a mystery.

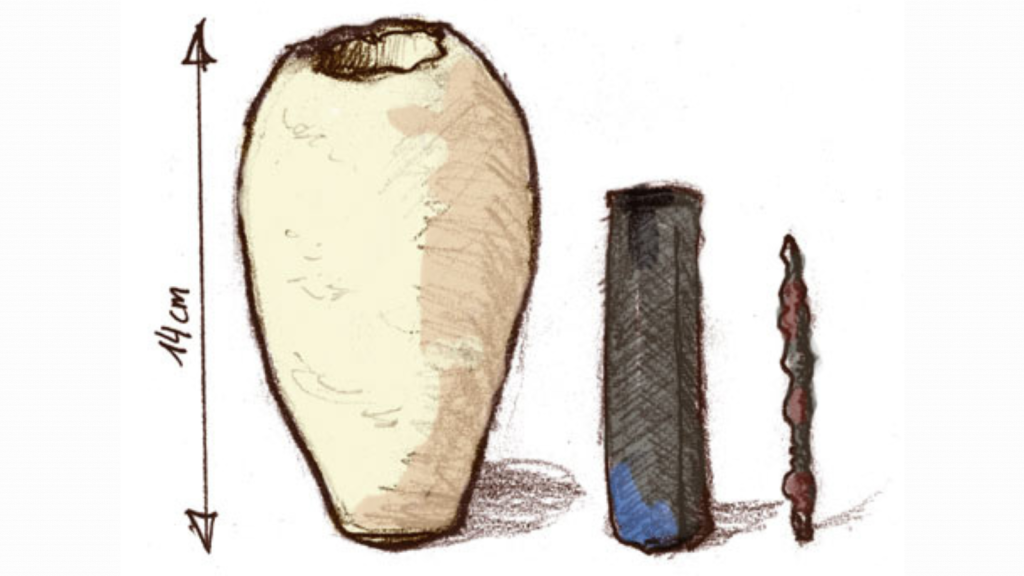

The Baghdad Battery

Found in Iraq, this clay pot is believed to be about 2,000 years old. It contains a copper cylinder and an iron rod, which could have been used to create an electric current when filled with an acidic liquid. While its purpose is debated, some think it might have been used for electroplating jewelry. If true, this would mean the ancients discovered electricity over 1,800 years before Alessandro Volta invented the modern battery.

Göbekli Tepe

This ancient temple in Turkey is rewriting our understanding of early human civilization. Built around 10,000 BC, it’s 6,000 years older than Stonehenge. The site features huge stone pillars arranged in circles, some weighing up to 16 tons. Creating this would have required advanced planning and engineering skills, way before we thought humans had developed such abilities. It’s making archaeologists rethink the origins of organized society.

The Lycurgus Cup

This Roman glass cup from the 4th century AD changes color depending on how light hits it. In reflected light, it looks green. When light shines through it, it turns red. This effect, called dichroism, was created by adding tiny amounts of gold and silver to the glass. It took until the 20th century for scientists to figure out how it works. The cup shows that Roman glassmakers had skills we’re only now beginning to understand.

Seismoscope

In 132 AD, Chinese scientist Zhang Heng invented a device that could detect earthquakes up to 500 km away. It looked like a large bronze urn with eight dragons around the outside, each holding a bronze ball. When an earthquake struck, the dragon facing its direction would drop its ball into a frog’s mouth below. This allowed the Chinese to respond quickly to distant quakes, long before modern seismographs were invented.

Archimedes’ Death Ray

Legend has it that the ancient Greek mathematician Archimedes created a weapon that could set enemy ships on fire using only sunlight. The story goes that he used a large array of mirrors to focus sunlight on Roman ships, igniting them. While many have tried to recreate this feat with mixed results, the concept shows an advanced understanding of optics for its time. Whether it worked or not, the idea was certainly ahead of its era.

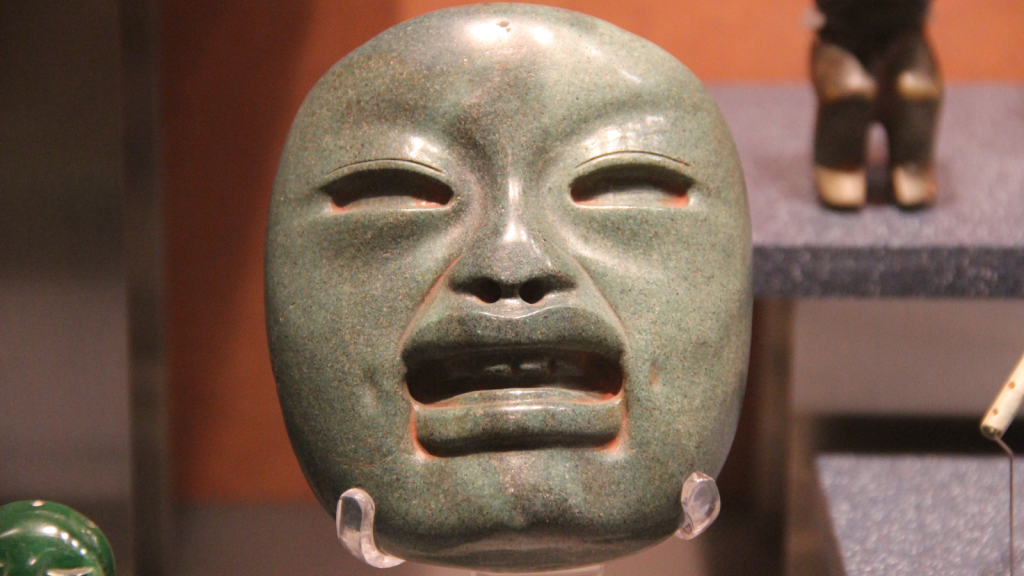

The Olmec Compass

The Olmec people of ancient Mexico may have invented the compass as early as 1000 BC. They carved large stone heads and found a way to orient them precisely. Researchers discovered that if you float a miniature version of these heads in water, they always turn to face magnetic north. This suggests the Olmecs understood magnetism and used it for navigation long before the Chinese invented the first known compass in 200 BC.

Aeolipile

This ancient Greek invention is considered the world’s first steam engine. Invented around 100 AD by Hero of Alexandria, it consisted of a sphere mounted on a boiler. Steam would enter the sphere and escape through two bent tubes, causing the sphere to spin. While it was treated as a novelty at the time, the aeolipile demonstrated principles that would later be used in the steam engines of the Industrial Revolution, nearly 1,700 years later.

The Nimrud Lens

Discovered in modern-day Iraq, this 3,000-year-old piece of rock crystal might be the world’s oldest lens. It’s of remarkably high quality, able to focus sunlight and magnify writing. Some researchers believe it could have been used as a magnifying glass or to start fires. Others think it might have been part of a telescope, which would radically change our understanding of ancient astronomy. Either way, it shows impressive early mastery of optics.

Ancient Indian Rust-Resistant Iron

In Delhi, India, stands an iron pillar that has puzzled scientists for centuries. Despite being over 1,600 years old and exposed to the elements, it shows almost no signs of rust. Metallurgists have found that it’s made of unusually pure iron with a high phosphorus content, creating a protective layer that prevents corrosion. This advanced metallurgy technique was lost over time and only rediscovered in the 20th century.

The Phaistos Disc

This mysterious clay disc from ancient Crete, dating to about 1700 BC, is covered in stamped symbols arranged in a spiral. It’s one of the earliest known examples of movable type printing, predating Gutenberg’s printing press by about 3,200 years. The meaning of the symbols remains unknown, but the disc shows that the concept of reusable, movable type existed long before its “invention” in medieval Europe.

Katy Willis is a writer, master herbalist, master gardener, and certified canine nutritionist who has been writing since 2002. She’s finds joy in learning new and interesting things, and finds history, science, and nature endlessly fascinating.