Space travel has long captured our imagination, but the reality of living beyond Earth’s atmosphere is far more complex than science fiction might have us believe. Our bodies have evolved over millions of years to thrive in Earth’s gravity, atmosphere, and magnetic field. When we venture into space, we expose ourselves to an environment utterly alien to our biology. From shrinking hearts to weakening bones, the effects of space on the human body are both fascinating and concerning. As we dream of Mars missions and lunar bases, understanding these changes becomes crucial.

Bones Turn to Jelly

In the microgravity of space, our bones lose density at an alarming rate. Astronauts can lose up to 1% of their bone mass each month, as the body sees no need to maintain strong bones without gravity’s constant pull. This loss is similar to severe osteoporosis and can lead to an increased risk of fractures. Even after returning to Earth, it can take years for bones to fully recover their strength. To combat this, astronauts use specialized resistance exercise equipment and may take calcium and vitamin D supplements.

Hearts Shrink

Without gravity’s challenge, the heart doesn’t need to work as hard to pump blood around the body. As a result, the heart muscle begins to shrink and weaken. Studies have shown that the heart can lose mass and become more spherical during long-duration spaceflight. This change can lead to dizziness and fainting when astronauts return to Earth and face gravity again. Cardiovascular exercise in space is crucial to maintaining heart health, with astronauts typically spending about two hours per day working out.

Eyeballs Get Squashed

Many astronauts experience vision problems in space due to a condition called Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS). The lack of gravity causes bodily fluids to shift upwards, increasing pressure in the head and eyes. This can lead to the flattening of the eyeball and swelling of the optic nerve, potentially causing long-term vision issues. NASA is developing special glasses and pressurized suits to help counteract these effects.

Immune System Goes Haywire

The space environment seems to confuse our immune systems. Some components become overactive, potentially leading to increased allergies and autoimmune responses. Other parts become suppressed, making astronauts more susceptible to infections. This immune dysregulation can persist even after returning to Earth, posing challenges for long-term space missions. Researchers are exploring ways to boost astronauts’ immune systems, including personalized probiotics and targeted exercise regimes.

Gut Bacteria Get Confused

Our digestive systems rely on gravity more than we realise. In space, the lack of gravity affects how food and fluids move through the gut. This can lead to changes in our gut microbiome – the collection of beneficial bacteria that aid digestion and support our immune system. These changes might contribute to digestive issues and could have long-term health implications. Space agencies are now studying how to maintain a healthy gut microbiome in space, including the use of specially designed probiotics.

Muscles Waste Away

Like bones, muscles atrophy quickly in microgravity. Without the constant work of opposing gravity, astronauts can lose up to 20% of their muscle mass in just 5-11 days. This muscle loss is particularly pronounced in the legs and lower back. Astronauts must exercise for hours each day to counteract this effect, but even with intense workouts, some muscle loss is inevitable. New research is exploring the potential of artificial gravity chambers to help maintain muscle mass during long space journeys.

Sleep Becomes Elusive

The lack of a regular day-night cycle in space can wreak havoc on astronauts’ circadian rhythms. The International Space Station orbits Earth every 90 minutes, meaning crews see 16 sunrises and sunsets each day. This, combined with the excitement and stress of space travel, often leads to sleep disturbances. Poor sleep can affect cognitive function and overall health, making it a significant concern for long-duration missions. To combat this, space agencies use special lighting systems that mimic Earth’s day-night cycle and provide astronauts with sleep education and monitoring tools.

Blood Flows Upwards

On Earth, gravity pulls our bodily fluids downwards. In space, this fluid shift reverses, causing blood to pool in the upper body and head. This can lead to puffy faces, nasal congestion, and headaches. It also reduces blood volume in the lower body, which can cause dizziness and fainting upon return to Earth as the body readjusts to gravity. Astronauts often wear special suction trousers called ‘Chibis’ to help redistribute blood to their lower bodies before returning to Earth.

Radiation Exposure Skyrockets

Earth’s magnetic field protects us from much of the sun’s harmful radiation. In space, astronauts are exposed to much higher levels of cosmic rays and solar radiation. This increased exposure can damage DNA, potentially leading to an increased risk of cancer and other health issues. It’s one of the biggest challenges for long-term space exploration, especially for missions beyond Earth’s protective magnetic field. Scientists are developing advanced shielding materials and medications to help protect astronauts from radiation damage.

Spine Stretches Out

Without gravity compressing the spine, astronauts can grow up to 3% taller in space. While this might sound appealing, it can be quite uncomfortable. The stretching of the spine can cause back pain and affect the fit of spacesuits. Upon return to Earth, astronauts quickly shrink back to their normal height, but the rapid changes can be disorienting. This temporary height increase has led to the development of adjustable spacesuits and seats in spacecraft.

Balance Goes Wonky

Our sense of balance relies heavily on gravity. In space, the vestibular system in our inner ear, which helps us maintain balance, gets confused by the lack of up and down. This can lead to space motion sickness in the short term. Even after returning to Earth, astronauts often struggle with balance and coordination for several days as their bodies readjust to gravity. Virtual reality systems are now being used to help astronauts retrain their balance systems before and after space missions.

Wounds Heal Differently

Surprisingly, cuts and bruises seem to heal more slowly in space. This could be due to changes in blood flow, increased radiation exposure, or alterations in cellular behaviour in microgravity. Understanding and mitigating this effect is crucial for treating injuries during long-duration space missions. Researchers are developing new wound dressings and healing techniques specifically designed for use in space environments.

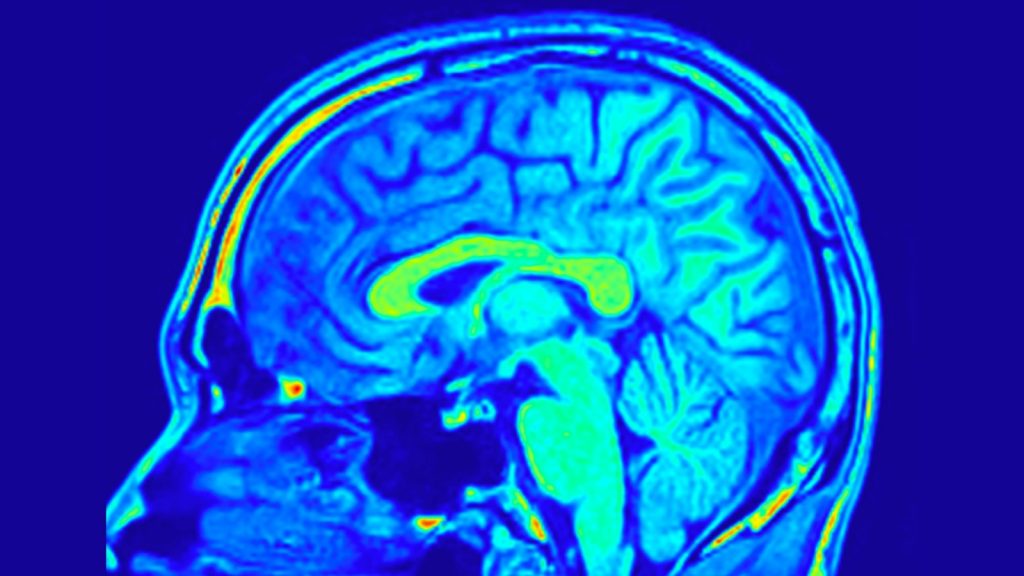

Brain Fluid Shifts

Recent studies have shown that the fluid surrounding the brain, called cerebrospinal fluid, increases in volume during spaceflight. This can lead to increased pressure inside the skull, potentially contributing to vision problems and the sensation of head fullness that many astronauts experience. The long-term effects of these brain changes are still being studied. Some scientists propose that a tilting bed that simulates gravity could help prevent these fluid shifts during long space missions.

Genetic Expression Changes

Fascinatingly, spaceflight seems to alter the expression of hundreds of genes. While the DNA itself doesn’t change, how genes are turned on or off can be affected. These changes seem to be related to stress responses, DNA repair, and immune function. Most gene expression returns to normal after returning to Earth, but some changes persist, raising questions about long-term effects. This research could have implications not just for space travel, but for understanding how environmental factors affect our genes here on Earth.

Cardiovascular System Remodels

The heart and blood vessels undergo significant changes in space. Blood volume decreases, and the heart becomes deconditioned due to the reduced workload in microgravity. Upon return to Earth, astronauts often experience dizziness and a rapid heart rate when standing. These cardiovascular changes are a major focus of research, as they could pose significant risks for long-duration space missions. Some researchers are exploring the use of artificial gravity chambers and specialized exercise routines to maintain cardiovascular health in space.

Katy Willis is a writer, master herbalist, master gardener, and certified canine nutritionist who has been writing since 2002. She’s finds joy in learning new and interesting things, and finds history, science, and nature endlessly fascinating.